Introduction by Prof Barry Hymer

As regular Chessable users know, our MoveTrainer technology embraces the powerful processes of spaced repetition, and we have written about ways of using this system most effectively in previous science blog posts. But we haven’t yet written a post about the very concept of memory and its general role in cognition and learning. I’m delighted therefore that Dr Jon Tibke has distilled the science for us into a very readable and accessible blog post this month. It is a version of a three-post series first published by Therapist Learning. Jon is a learning scientist working across the educational and health sectors, who has a longstanding interest and expertise in the interface between the mind and behaviour, drawing especially on findings from neuroscience.

There are a few core and wonderfully optimistic take-homes from Jon’s piece which hit the spot for me in my personal Chessable practice. One is that one’s memory capacity is close to infinite—even for we amateurs with limited time for practice and repetition. I needed reminding of this as I started working my way enthusiastically through GM Pepe Cuenca’s brilliant and comprehensive Chessable course on the Philidor. The course is vast and will take me some months to complete, and the disturbing thought occurred to me as I made my painstaking progress, ‘What if I can’t retain it all? Is there any point learning something which is going to need to be relearned all over again?’ Well, as Jon’s post reminds me, even my aged brain CAN retain it all, and the point of learning something is that the price of retention is eternal revisiting. That’s the genius of MoveTrainer, compared to my old narrative methods of learning openings from books: whereas once I finished a book I knew that I really needed to re-read it, of course I didn’t—my brain was more eager to explore novel material. It felt like an admission of failure that the lines I’d ‘learned’ had somehow evaporated. Chessable courses inhibit evaporation by building in constant active review. Of course this doesn’t mean that the learning is always easy – some of those infernal deceptively-similar-but-subtly-different Philidor Endgame lines (where White exchanges pawns on e5 and trades queens) can test the patience of Petrosian, and these are the moments where the Difficult Moves feature on PRO comes into its own.

Another core takehome for me is in Jon’s synthesis of Kenneth Higbee’s work, including the salience of meaningfulness in supporting memory, and the role of patternmaking organisational strategies. Every chessplayer will be able to see the connections here, and it’s one of the reasons I prefer to adjust my settings to ‘All moves’ when learning and reviewing something – yes, it can take a few tedious seconds to play through the initial sequence ‘mindlessly’, but it’s actually not mindless at all – it’s helping me embed and contextualise the terminal stages of a sequence, and put it into the context of an actual game – “Ah – this is the line where I need to look out for the chance to sac my knight on e4 and pick up White’s bishop on c4 with a pawn fork in handsome return”. Giving a line meaning and hooks into existing knowledge is all-important – see also my post on doing ‘dumb stuff’ and implicit learning.

Which is the link to my final introductory thought: MoveTrainer’s exploitation of SRS doesn’t mean other memory strategies are irrelevant. We’ve had an interesting exchange with a Chessable user recently on possible moves into memory-palace territory (see Jon’s account of Robert Winston’s experiment) – to augment SRS gains – and look out for future descriptions of how we’re working with international memory champions to see what resonances there can be for us in making improvements to our offer.

But for now, over to Dr Tibke:

The salience of strategy

No question that memory is a crucial thing, for all kinds of reasons. I’m going to start with some groundwork before getting into some of the specifics that are worth considering in general and in reference to your individual chess strategies.

A true story, starring me, to get us started. In 2015, for the second time, I did a six-week learning workshop tour in India. This second tour was focused on memory and consolidation of learning. As this tour was around the time of International Pi ( π ) Day (March 14 – 3.14) I started the workshops by reciting Pi to 14 decimal places, with a participant writing them up for all to see and another checking them on a mobile. My audiences thought I was slowly and dramatically dredging the numbers from the depths of my memory, but the speed was actually dictated by my going through a 14-word sentence in my head, in which the number of letters in each word represented the numbers I needed to recall. Interestingly, after a few workshops I didn’t need the sentence as by then I could reel off the numbers. So what I demonstrated was not super memory but an effective memory strategy, with the added bonus of quickly convincing my audiences that I really did know something about this.

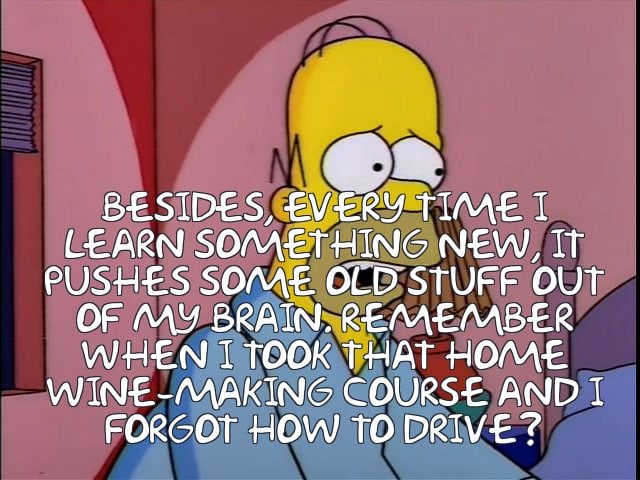

Analogies and metaphors can be useful things and we use them in many contexts, but they can sometimes be an unhelpful self-fulfilling prophecy. Every time you think or say that your memory is like a sieve, you’re not helping yourself! All of us actually have boundless memory – no research has ever succeeded in establishing any kind of limit. So when Homer Simpson declared that ‘Every time I learn something new it pushes some old stuff out of my brain,’ he was wrong. His evidence was anecdotal: ‘Remember when I did that home winemaking course and forgot how to drive?’

NOTE: Want to read more articles by Prof Barry Hymer?

The Alluring Illusion of ‘Learning Styles’ in Chess

Which Beautiful Game, Exactly?

Closing the gap: How gender-blind is chess, actually?

Thinking Moves: Why It’s Worth Thinking About Your Thinking

Selective sponges

It’s also not accurate to describe memory, as I often hear said about children, as a sponge, soaking up everything. My dad, lovely man that he was, put a lot of energy during my childhood into reminding me to close doors, preferably by using the door handle. No sponge in my head was soaking that up and here’s why: it didn’t matter to me and I didn’t know why it mattered to my dad. As neurobiologist John Medina writes in Brain Rules (2009), we don’t pay attention to things that we find boring. Important lesson there: if you are approaching any learning in a way that bores you, then you will indeed remember only a limited amount, but that does not mean there is something wrong with your memory. Incidentally I can recall with ease, without any attempt to learn them, all my dad’s witty catchphrases and those very, very few occasions as a child that I heard my dad use a swear word. Now why is that?

You’ll be able to answer that question. I’d like to conduct a small test now, so please do something else for a few minutes, such as put the kettle on and make a cup of tea to enjoy in the next section. Switch off from what you’ve read so far.

Welcome back. You do of course remember something from what you’ve read so far? Homer Simpson? That’s not just me being flippant. You may initially not have recalled anything, but may well then find that the mention of Homer Simpson brings back the cartoon and the comment.

This tells us a lot about how memory works. In simple terms, things get broken down and stored in different areas of the brain. We store different things in different ways in different places, but all these things can connect via networks. So you may not always need to remember heaps of details if the right triggers can help you recall what you need. And don’t panic that it doesn’t always happen instantly. We’ve all had the experience of thinking something is forgotten, only for it to reappear a little later, in there somewhere all along.

Building palaces

Professor Robert Winston is a top surgeon who also became a popular TV science presenter. He once did a programme with memory champion Andy Bell (The Human Mind, Episode 1, BBC 2003). Andy discusses his strategies for amazing feats of memory, such as associating seemingly random sets of numbers with similar sets of numbers, such as athletics records. They conduct a memorising experiment that would work for many things and quite possibly for sequences of chess moves. Andy gives the professor a list of 29 random things and asks him to assign them to the rooms of his house. As I recall, he pairs some of them up, so ‘swan’ and ‘piano’ are put together as a swan playing the piano in the dining room.

After a very busy day travelling across London and performing surgical procedures, the professor returns home and despite his apparent doubts that he will remember the items he successfully recalls them all, seated at his kitchen table working his way round his house in his head. OK, sceptics can say this was a bit staged and maybe even edited, but the strategy is certainly useable. Note the word ‘strategy’ again. Interestingly, different ones work for different people, largely due to what we connect with, again to do with wider memorable features such as with whom, where, when, we created the memory aid and how we subsequently used it. We’ll return to connecting later.

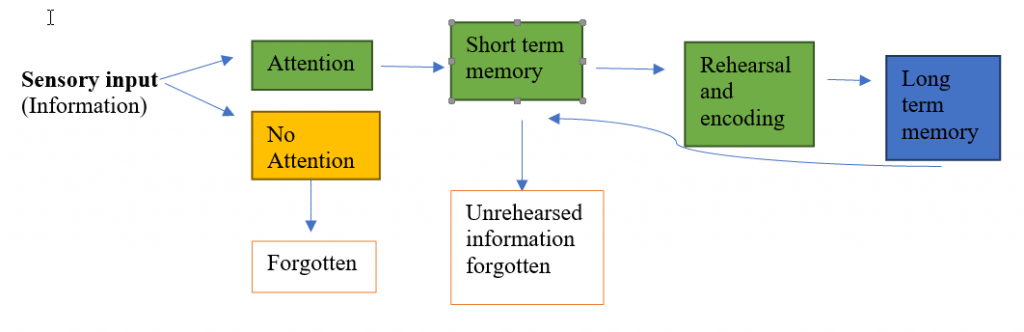

This seems to be about enriching or rehearsing pieces of information so that there is plenty of ways our brains can recall them. There are a number of models and theories, but in essence it goes something like this:

The value of infinite variety

Another thing to raise here connects with what I have previously said about needing to interact in a variety of different ways with information that we are trying to learn, in order to consolidate it somewhere in memory. With this in mind I’d like to introduce you to American psychologist Robert Gagné and what is known as Gagné’s Five Domains of Learning. Gagné was not the first nor the last to theorise about this, but I think his domains certainly chime with professional knowledge, as we often need to use our knowledge and information in different ways, which therefore gives us a variety of ways to reinforce that knowledge. I’ll let you ponder on whether they have traction in a chess context.

Intellectual: working with concepts and rules to solve problems

Motor: using movements efficiently

Verbal: articulating information

Cognitive: creating new solutions, managing own thinking and learning

Attitude: chosen behaviours

To round off this exploration of memory, I’m going to draw a few things together and throw in a few more memorisation principles.

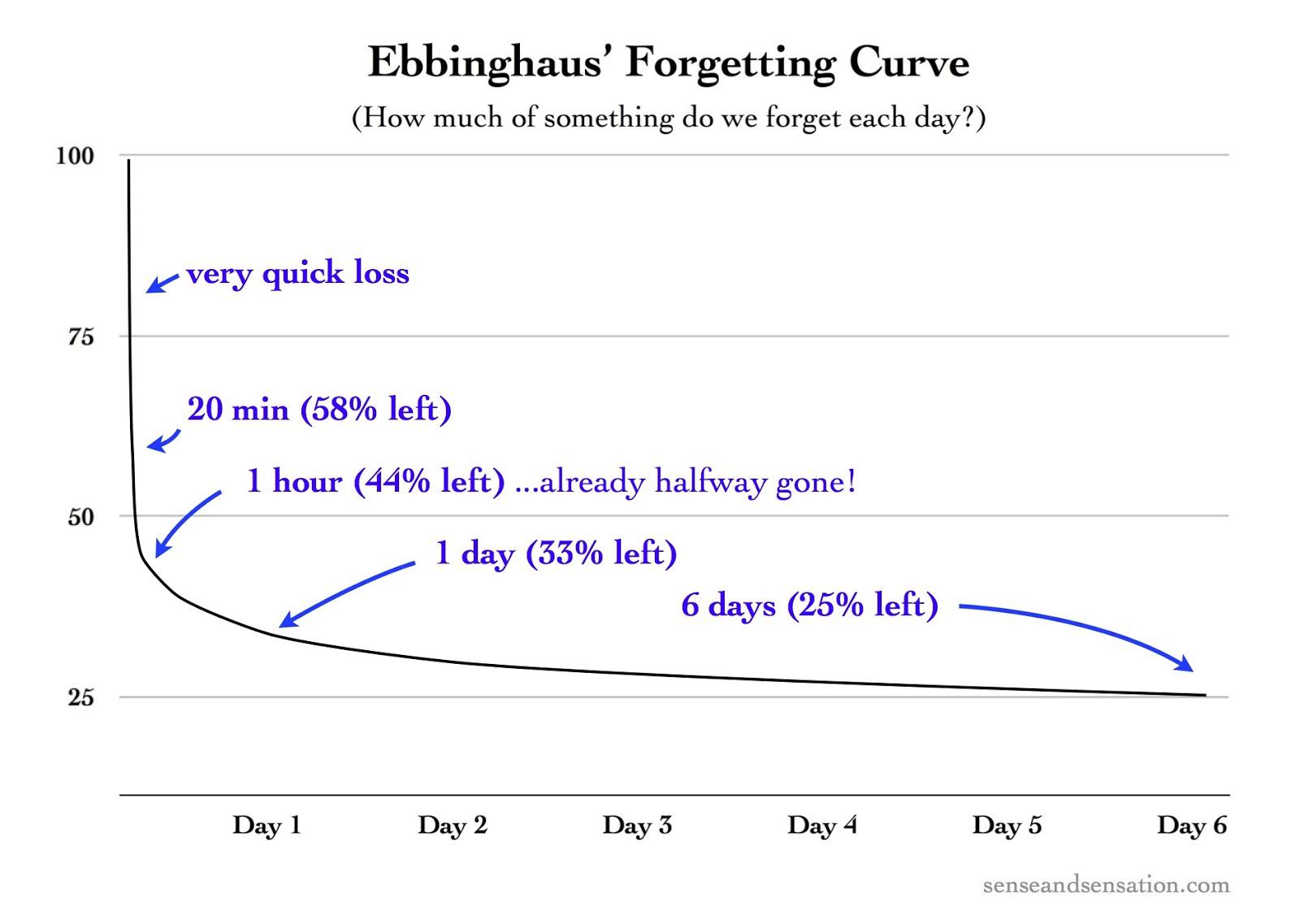

No apologies for going over a few things – that’s a key part of memorisation. You have to review, reconsider, re-set the challenge and so on. If you expect it to ‘stick’ in one go there’s a good chance you will be disappointed. Ebbinghaus’s Forgetting Curve (1885, so not a new idea), neatly summarises how quickly we are likely to forget something that we have only encountered once.

(Wikimedia.commons)

So we’ve established that staggered repetition, but not boredom, is important and that repetition should involve using information in different ways. Gagné and others have attempted to identify the types of activity we might use to achieve this.

Let’s briefly consider how these might assist us, using a personal example of mine, but please quickly re-work this with one of your own. I am currently reading John Gibbons’ latest book, The Vital Nerves. Clearly, there is plenty of intellectual challenge in its contents, so domain one is very evident. I can add a motor dimension myself (domain two), physically plotting nerve pathways etc on myself, going through the movements that different nerves control etc. That leads us to something called embodied cognition, but that’s a whole different subject. Domain three could involve explaining some of what I have learned so far to someone else or record myself attempting to explain and then review that. Or I might attempt to explain it in a different format, such as a diagram or a picture. For domains four and five I could think about how this new information might assist with current clients, or with a client with whom I suspected a nerve issue but lacked the depth of knowledge to pursue that further. In this scenario the domains combine or overlap. How much does the client need? In what form? Which clients? When would it be helpful? Am I just parading knowledge for its own sake (not a good behaviour choice)?

Whatever approach I take, one thing is clear: as much as I may get a great deal from reading John’s book, if that is all I do I am likely to remember only a small amount of what I have read.

It’s about strategy, remember?

All of this leads back to a central point: we need strategy. Most of us have a few ideas for this that we have picked up along the way and I strongly advise that you continue to get to know your own memory in this regard, gaining a deeper understanding of the types of strategy that work for you. In Kenneth Higbee’s view, strategies work through some basic principles. Firstly, meaningfulness, whether that is relevance to you or your clients, connections with things you have learned before, patterns that you recognise. Secondly, organisation. Higbee uses the dictionary as an example. How come you can find the words you’re looking for in a dictionary? OK, pretty obvious, but take away the organisational role of alphabetical order and dictionaries would be chaotic, annoying things. So what organisational rigour can you impose on information you are trying to memorise? How can you group it? Where are the unexpected connections and associations? Like the Robert Winston experiment, you can also create the associations for yourself.

Visualisation is the next principle. We often try to visualise things to recall them. I have known students remember huge amounts of information by turning it into a picture. The same picture might not work for someone else, of course and I should also mention that a small percentage of us simply do not think in pictures at all, so this approach won’t help. The final principle is attention. You won’t remember details that you didn’t pay attention to. There is a wider point here, about multitasking. Basically, with complex, challenging information and learning, it needs your undivided attention. Cognitively, multitasking is actually just switching rapidly between things, with mental energy wasted each time you have to re-connect. Though many of them probably never explained why, it turns out there was good reason that some teachers insisted on your undivided attention.

Final thoughts

Returning to where we started, let’s remind ourselves that memory is not finite, is not a single structure, is not always easy, takes practice, regular use, planning and strategy. ‘Eyewitness’ testimonies show us that it is not always reliable either, so be kind to yourself as stressing about it or accusing yourself of having a ‘bad memory’ (you don’t have) won’t help. About 20 years ago I sat my kids down to watch the Steve McQueen film The Great Escape. It must have been Christmas Day or Boxing Day. I repeatedly told them that the ending was brilliant. This was because as I remembered it, Steve McQueen soars over the barbed wire on a motorbike, to freedom in Switzerland. I’ll never recover from my children’s disappointment when Steve and the bike get tangled in the barbed wire and returned to the prison camp. Sometimes we remember what we choose to remember. I’m never living that one down.

Keep learning!

Jon

References

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885) Memory: a contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Dover

Higbee, K, L. (2001 ) Your Memory: how it works and how to improve it. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press

Gagné, R. (1985) The Conditions of Learning. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Medina, J. (2008) Brain Rules. Seattle: Pear Press

Further Reading

As I’m sure you can imagine, this is a huge field of research, from many disciplines and angles within them. This very short list is an attempt to reflect that. Herein lies some very challenging reading!

Frank, C., Land, W. M., Popp, C. and Schack, S. (2014) Mental Representation and Mental Practice: experimental investigation on the functional links between motor memory and motor imagery. PLoS ONE 9(4):e95175

Schacter, D. L. (2013) Memory: from the laboratory to everyday life. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2013 Dec: 15(4) 393-395

Stickgold, R. and Walker, M. P. (2007) Sleep-Dependent Memory Consolidation and Reconsolidation. Sleep Medicine 8(4): 331-343.

Websites

Two very interesting places to look:

This site updates daily, with summaries of copious amounts of research.

https://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/neurok.htm

Don’t be deceived by the title here (Neuroscience for Kids). Eric Chudler at Washington University maintains this superb resource, with no dumbing down but with great challenge for young readers (and older ones). A great tool in understanding the brain.