The Chessable Research Awards for the Fall 2023 cycle had two winners, undergraduate student Aditya Gupta and graduate student Denise Trippold.

In this guest blog post, Woman FIDE Master Denise Trippold writes about her research, which was supervised by Roland H. Grabner (University of Graz, Austria) and Merim Bilalić (Northumbria University, United Kingdom). The aim of her master’s thesis is to examine the relations between chess skill and different psychological variables to identify psychological indicators of chess talent.

Talent Identification in Youth Chess Players by Denise Trippold

On my journey as a chess player and coach, I have met very talented children and youth chess players. I wondered why they were already so good at chess at this early age. Did they just practice a lot? Or were they very intelligent or motivated? These considerations brought me to the topic of my research: What kind of variables can predict chess skill?

Nature vs. Nurture in Chess

There is a heated debate in psychology about whether innate talent or practice is the most important predictor of expertise in different domains.

Anders Ericsson was probably the biggest advocate of the so-called “deliberate practice” which is characterized by highly structured individual activities, the goal of increasing performance, and instructive feedback (Debatin et al., 2021). He claimed that deliberate practice is essential to become an expert in a specific domain (Ericsson et al., 1993). In a meta-analysis by Hambrick et al. (2014), a third of the differences in chess skill among the participants could be explained by differences in the number of hours dedicated to deliberate practice.

Chess as a cognitive sport requires a lot of cognitive abilities, e.g. logical reasoning for the evaluation of a position, or spatial imagination to think several moves ahead. Furthermore, a specific minimum value of intelligence seems to be important in order to use learning opportunities to an optimal amount, and thus, increasing one’s chess skills. In their meta-analysis, Burgoyne et al. (2016) examined 19 studies and found a correlation of r= .22 between cognitive abilities and chess skill, which can be described as a moderate correlation. In addition, cognitive abilities were a stronger predictor of chess skill in youth chess players compared to adult chess players.

What else could influence the chess skill of children and youth chess players? Motivation and personality traits could impact the amount of chess-related practice. If chess is fun for you, you will probably spend more time playing and studying compared to those who find it boring. Bilalić et al. (2007) examined children and their personality traits. The researchers found that children with lower values in agreeableness had higher chess skills than children with higher values. Being agreeable is distinguished by being kind to other people or trusting in other people. Besides that, emotional abilities could be helpful to control one’s emotions during a chess game at a tournament. Dealing with ups and downs during a game or handling stressful situations in time trouble requires a certain kind of emotional regulation, which can lead to better performances. Grabner et al. (2007) identified emotion expression control as an important predictor of chess skill in a study with adult participants.

Especially for youngsters, external support is essential, e. g. the help of their parents or at least the possibility to attend a chess course. Ziegler and Baker (2013, as cited in Debatin et al., 2015) differentiate in their educational capital approach economic, cultural, social, didactic, and infrastructural educational capital which can influence the developmental process. Debatin et al. (2015) identified resources according to this approach in the biographies of two of the strongest players in the world, Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana. Lastly, according to the goal setting theory of Locke and Latham (1990) chess players with higher goals could be motivated to practice more chess, and thus perform better than chess players who set themselves lower goals.

Study design and method

The aim of my master’s thesis is to examine the relations between chess skill and different psychological variables to provide a first step in the identification of psychological indicators of chess talent.

Data of 83 children and youth chess players from ten to seventeen years and national Elo rating, which was used to quantify chess skill, from 800 to 2250 were collected with a questionnaire. The sample included 25 girls.

One test session took about 60 minutes and involved paper-pencil tests covering a broad range of psychological variables that may serve as talent indicators of chess. These were identified based on previous research and discussions with expert chess players.

As there are only a few studies who examined children and youth chess players, multiple variables were assessed. Specifically, data about the following variables pictured in the table were collected.

| Category | Variables |

| Chess related activities | cumulated hours in training alone, training with coach, playing chess for fun and indirect chess related activities (e.g., watching chess streams), number of tournament games |

| Cognitive abilities | numerical, verbal, and visual-spatial intelligence, arithmetic factual knowledge, and arithmetic procedural knowledge |

| Personality | Big Five, need for cognition, hope |

| Motivation | performance motivation, importance of chess, training motivation, enjoying playing chess |

| Environment | support of parents, chess knowledge in family, external resources (chess club, financial resources, etc.), attendance to chess course in school |

| Goal | highest goal in chess |

| Emotional regulation | masking of emotions, regulation of one’s own emotions |

| Personal data | age, sex, national rating, number of games in chess tournaments, age at which was joined to a chess club |

Table 1. Assessed categories and respective variables.

Results

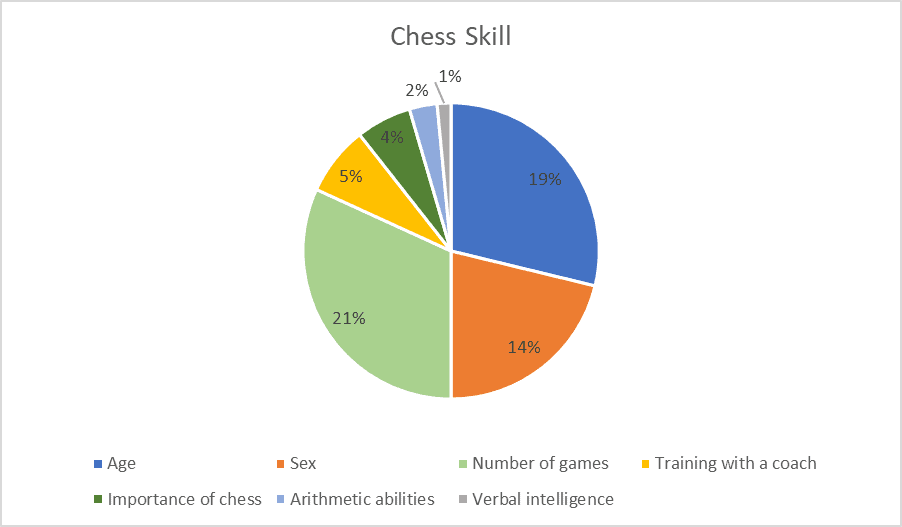

A regression analysis revealed that – after age and sex – chess related activities are the best predictor of chess skill. Specifically, the number of games and the accumulated hours in training with a coach had the highest impact. After that, arithmetic abilities played an important role in predicting chess skill in the study, followed by verbal intelligence, and the importance of chess. Overall, those mentioned variables explained almost 70 percent of differences in chess skill. The following pie chart shows how much each variable contributes to explaining chess skill in the study:

Table 2. Potential talent indicators in chess.

Surprisingly, neither the personality traits or emotional abilities nor numerical or spatial-figural intelligence had a significant impact in explaining chess skill once the practice and intelligence were accounted for. Furthermore, higher goals did not lead to more chess-related activities. Similarly, the conclusion cannot be drawn that chess players with higher support from their environment have higher ratings than chess players with lower support.

Discussion

Due to the use of correlational tests, it is not possible to draw causal conclusions. For example, we can say that verbal intelligence correlates with chess skill, but we cannot say that higher verbal intelligence leads to higher chess skill or vice versa. Therefore, longitudinal research is necessary. Fortunately, this study was only the first data collection – a second one is planned by university professor Roland H. Grabner (University of Graz, Austria).

Furthermore, it should be noted that a ceiling effect appeared in the test results of numerical intelligence, because 74 participants scored 18 or more points from possible 21 points. This could be the reason for not finding a correlation between numerical intelligence and chess skill in the regression analysis because all participants scored quite high. This leads to the assumption that children and youth chess players have high numerical intelligence in general.

The study emphasizes the importance of playing a lot of tournament games and taking chess lessons with a coach in order to become a strong chess player as a child or adolescent. Verbal intelligence and arithmetic abilities could serve as potential talent indicators. To measure the verbal intelligence, the participants had to match a given word to another word with the same or a similar meaning. E.g. if the given word was “house” and the answer options “garden,” “roof,” “building,” and “town” – the right answer was “building.” To find the solution, the children and youth chess players could have used cognitive abilities, such as logical thinking, and problem-solving abilities, which are also helpful in chess. Same goes for the arithmetic abilities test, where the participants had to calculate simple multiplications and subtractions. Furthermore, when chess plays an important role in children’s lives, one could assume that they spend a lot of time playing and/or studying it, which could lead to higher chess skills.

However, as almost only screenings and short versions of tests were used, further research is needed to consolidate the findings. Lastly, we should not forget about the individuality of children’s chess careers.

References

Bilalić, M., McLeod, P., & Gobet, F. (2007). Personality profiles of young chess players. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(6), 901–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.08.025

Burgoyne, A. P., Sala, G., Gobet, F., Macnamara, B. N., Campitelli, G., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2016). The relationship between cognitive ability and chess skill: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Intelligence, 59, 72–83. DOI: 10.1016/j.intell.2016.08.002

Debatin, T., Hopp, M., Vialle, W. & Ziegler, A. (2015). Why experts can do what they do: the effects of exogenous resources on the Domain Impact Level of Activities (DILA). Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 57(1), 94-110. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/1873/

Debatin, T., Hopp, M. D. S., Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2021). The meta-analyses of deliberate practice underestimate the effect size because they neglect the core characteristic of individualization—an analysis and empirical evidence. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02326-x

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

Grabner, R. H., Stern, E., & Neubauer, A. C. (2007). Individual differences in chess expertise: A psychometric investigation. Acta Psychologica, 124(3), 398–420. DOI: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2006.07.008

Hambrick, D. Z., Oswald, F. L., Altmann, E. M., Meinz, E. J., Gobet, F., & Campitelli, G. (2014). Deliberate practice: Is that all it takes to become an expert? Intelligence, 45, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.04.001

Interested in research?

The Chessable Research Awards are for undergraduate and graduate students conducting university-level chess research. Chess-themed topics may be submitted for consideration and ongoing or new chess research is eligible. Each student must have a faculty research sponsor. For more information, please visit https://www.chessable.com/research_awards