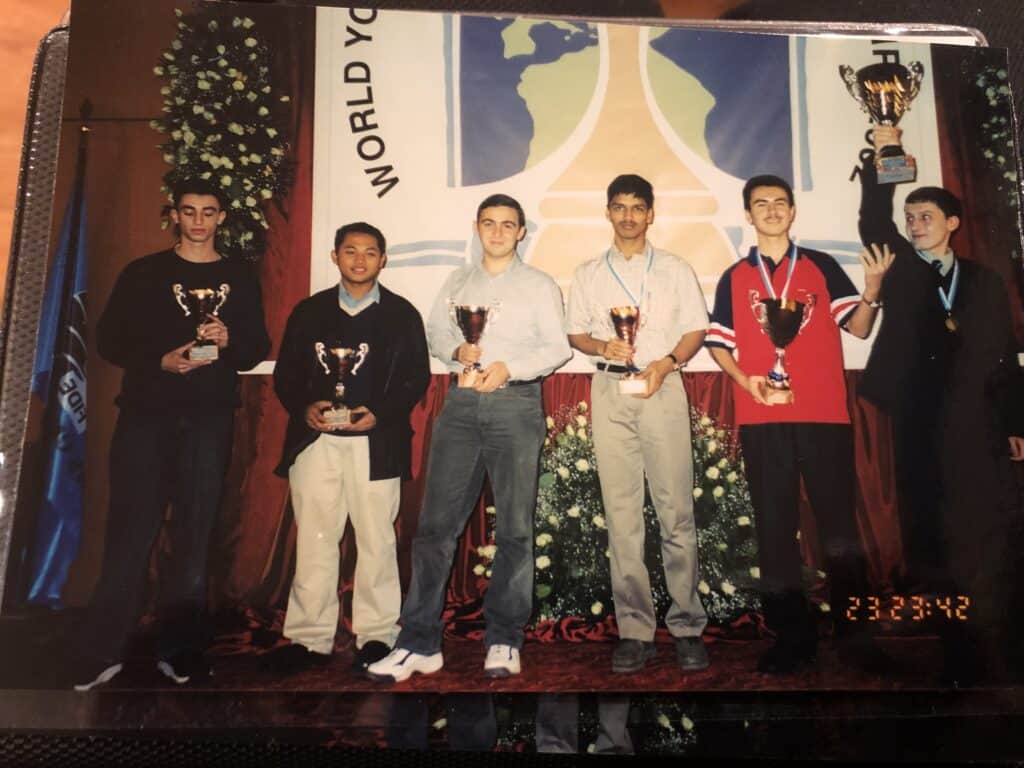

This is a guest post by International Master Dmitri Shneider. Dmitri is Chief Financial Officer of Play Magnus Group (PMG), a publicly traded company on the Euronext Growth Oslo market. In his younger days, he was a top ranked junior chess player. He has represented the United States in over a dozen World Youth and Pan American Youth Championships, having multiple top 10 finishes and two gold medals. In 2003, he was awarded the Samford Fellowship, an award given to the top United States chess player under 25. Since leaving the competitive chess world, IM Shneider has gone into the field of investing, working for J.P. Morgan Private Bank for nearly 12 years, most recently as Executive Director of Equity Strategy in Hong Kong, focusing on U.S. and Asian stock markets. He was an early investor in Chessable and joined full-time as Chief Operations Officer in 2019. He is a CFA® charterholder.

What do chess and investing have in common?

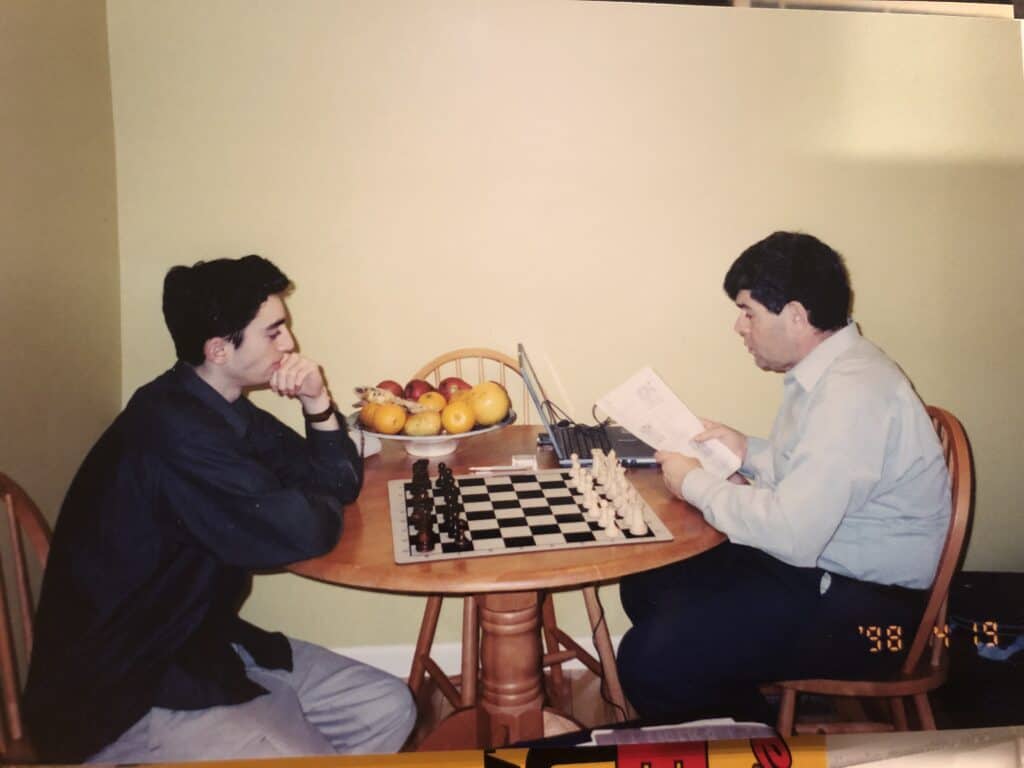

As a brief background, chess was my life from the age of 8 until my retirement at the age of 23 when I went to go work in the field of finance. I did everything I could to be the best. I trained for hours on a consistent basis both on my own and with top coaches, played online daily and regularly over the board both in the U.S. and abroad. I loved the idea of making progress, gaining rating points, titles, winning tournaments but most importantly, trying to play aesthetically pleasing games and moves. It didn’t happen nearly as often as I’d like but when everything comes together, it can be as memorable as anything else in life!

Chess helped me get my first job in early 2008, an analyst role at J.P. Morgan. It was not an easy time in finance as the U.S. housing crisis was in full swing, but the managing director who hired me appreciated that I was a chess player and believed that even though I had no experience (I spent most of my prior summer’s playing in chess tournaments), that I could learn the investing business. It’s nearly impossible to fully learn investing, just like it is nearly impossible to learn chess. Both have art, science and sport components which I fully embraced. I ended up spending nearly 12 years at J.P. Morgan, across two continents and reaching the title of Executive Director. My main tasks were to diligently research and prepare investment recommendations, earn returns for clients to the best of my ability, and educate them on the impact of the ever-changing global landscape and trends on their portfolios. As in chess, it was great to always be learning something new and there were few better feelings than getting the thesis right and having the recommendation play out as planned. Unlike chess, there were many more things out of our control, but I would like to share some similarities between investing and chess:

#1 – Comfort zone and circle of competence

Grandmaster Alex Colovic wrote a fantastic column earlier this year talking about the benefits of being in the “comfort zone.” His main point was that while it is good to be adventurous and broaden our horizons, it is much easier to play positions when we feel more comfortable in them. I would always rather take a slightly worse position out of the opening if the pieces and pawn structure were dynamic, rather than a slightly better position where I had to grind out long, strategic and often subtle maneuvers. Some players love that as they don’t feel as comfortable in sharper positions, so there’s no right or wrong answer!

The goal is to learn and explore but it’s much more effective when starting with some understanding of the underlying types of positions. This doesn’t mean that one should play only the same line of the same opening all the time, but it could mean that one experiments with different lines of a rich opening like the Ruy Lopez or Queen’s Gambit where there are many ways to deviate and learn new ideas…or it could mean that if one realizes that they like the isolated queen’s pawn positions, they try out different openings with that theme. Not sure where to start? Watch the games of your favorite players and see if the moves make sense to you and give those openings a try. (How? Just sign up for a bunch of free chess opening courses here on Chessable and go through them one by one.) It’s okay to try a few before “settling down” and choosing a main opening.

Investing is very similar in that it may be fun to invest in trendy stocks, but if one can’t handle the volatility of the imminent swings or is not comfortable in understanding the business dynamics in that industry, it will be very tough to execute the long-term plan and there’s a big risk of making a mistake either in selling too soon or not realizing the fundamentals – and the original thesis has changed. There will always be new trends, new companies, and new market leaders. Unless one has a trusted advisor or the time and competence to study them closely, it’s very difficult to outcompete the professionals who do this on a daily basis.

The key is to find a circle of competence or a strategy and stick with it. Maybe, the most important thing is to “know the game you’re playing” and be mindful of the strategy and be disciplined in following it. Many experienced investors have been burned by going outside of their usual strategy to follow a trend (or try to predict unpredictable macroeconomic events), and/or not being disciplined in following through on their strategy because of emotions or external influences.

#2 – Pattern Recognition, Tactics, and Pawn Structures

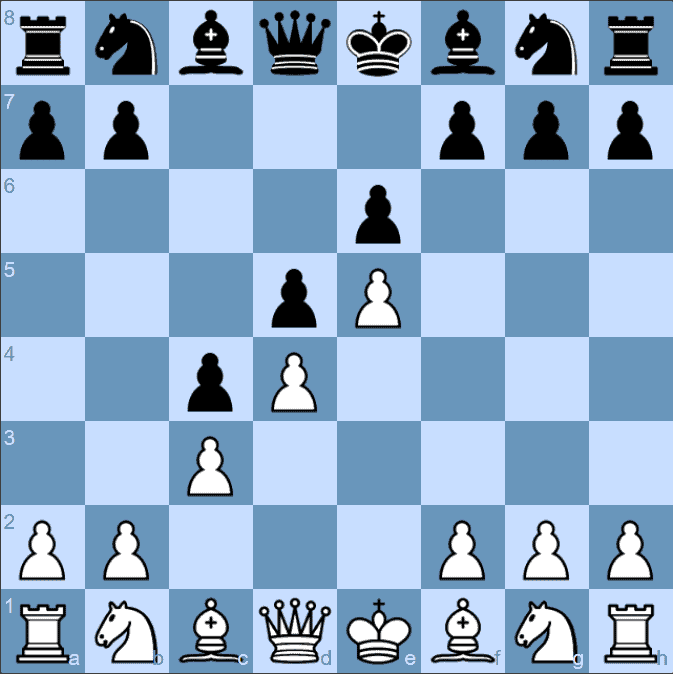

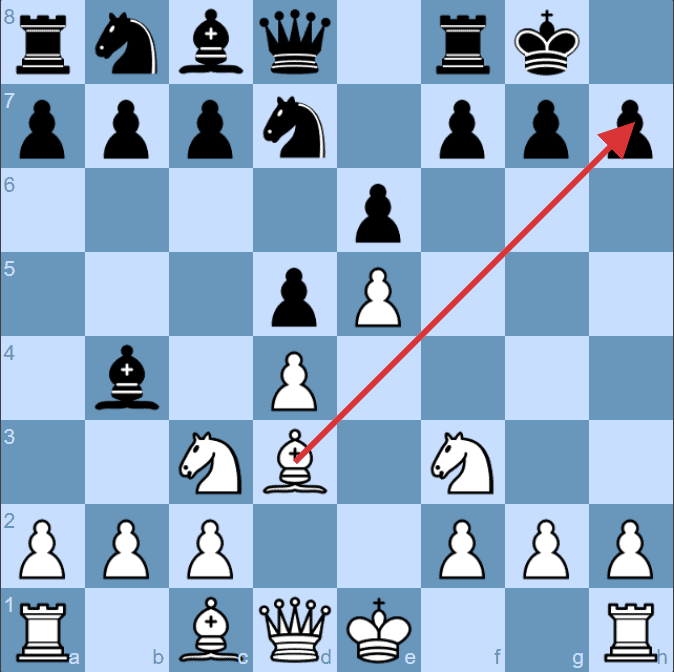

Pattern recognition is probably the first skill that people outside of chess kindly bestow on chess players. It is true that in a game as complex as chess, it is very beneficial to learn as many patterns as possible to try to simplify your life. This starts with knowing the basic checkmate patterns, attacking motifs, and ways to convert an endgame, but also the underlying pawn structures that can help dictate the piece and positions and ensuing plans. For example, there’s a known rule for pawn chains such as in the French: the White pawns on c3, d4, e5 vs. Black’s pawns on d5, e6 mean that White usually should attack on the kingside (and black on the queenside). This is because White has more space and can more easily attack there.

In this example, a usual tactic would be 1.Bxh7 Kxh7 2.Ng5+ Kg8 and 3. Qh5 threatening mate (known as the Greek Gift sacrifice).

If someone has trained their tactics they should see this very quickly; however, the next level is to be able to steer the game into the direction of being able to achieve such a pawn structure rather than falling into it by accident. Going over games of top players past and present is quite helpful in this regard. The pawn structures are kind of like a map. Without knowing where you are and where you’re going, things become much more difficult!

Investing is similar in many ways. If one studies enough companies, reads enough annual reports, and sees enough market cycles, some things become more apparent. It is often quoted that “history does not repeat, but it rhymes.” No two investments are exactly the same but they may have characteristics that may allow the diligent investor to improve their odds of making the right decision. For example, one pattern is that investors go too far in either direction of positivity or negativity. So if valuations of certain sectors get to multiple standard deviations above or below the historical norms it could mean that the companies in the sectors are “special” or that the valuation methods have changed, or more likely there will be some reversion to the mean. It doesn’t mean it’s easier to time the decisions but first identifying the map can help with the orientation!

#3 – The Art of Being Decisive vs. Staying Calm Under Pressure

One of the toughest things in both chess and investing is knowing exactly when to act and when to stay put and follow the strategy. Contrary to some beliefs, in chess it is not necessary to calculate every move every time it is your move. I’ve often found that there are only several moments in a chess game where a position is critical and one has to decide whether to change the pawn structure, make a dynamic trade or sacrifice for an attack. The rest of the time it’s usually just following through the original plan and making sure we don’t miss anything too important. Often we give our opponent too much credit or second-guess ourselves and waste a lot of time and energy on unnecessary moves. Or worse, we start making big strategic bets or tactical sacrifices before everything is ready. It’s not easy when the opponent is putting pressure on us, but often following our strategy is less risky than going into complications when it may be in our opponent’s favor.

In investing, the art of action vs. inaction may be the most important. Many times it’s just as beneficial for returns in not selling a great company that can compound returns over the long-term than trading around it just “to do something”. Or altering your portfolio allocation in contrast to a previously decided on strategy only to try to capture some near-term returns. It’s easy to get spooked by elections, Brexit, or get carried away by some other short-term hype. The key is to always be honest with yourself if you are following your strategy or making changes because of external influences.

So when should one be decisive? There’s no clear formula, but here are a few rules of thumb that I found helpful:

1) When the thesis on the position or investment has changed. Something happened; there’s new information, and if not rectified quickly it could really go downhill quickly.

2) When you’ve done your homework and are prepared. All the pawns and pieces are set up, there are many checks on the checklist and it’s time for action – in other words, it’s time to take advantage of the opportunity.

3) When the opponent is putting pressure and a trade of their attacking piece or an exchange sacrifice flipping the dynamics would be useful. The investing corollary could be that a certain sector is showing signs of deteriorating long-term fundamentals and it’s time to investigate whether a change in the asset allocation is appropriate.