Chess beginners have a lot of catching up to do.

They need to learn some basic strategy, which is intimidating for its extent and complexity. But tactics will decide 95% of their games, so it’s essential to drill those. And sometimes they reach the endgame…there’s that too.

However, after a certain level of competence, controlling the center, developing your pieces, and taking your king into security stops being enough to get you a game. Knowing your openings becomes a must. Otherwise, making it to the middlegame and applying all that strategy and tactics can prove difficult.

That’s when the headaches start. Opening preparation is the dark beast of chess study. Mainly because it takes a lot of time, and it never ends. On the other hand, it’s one of the most rewarding areas in chess and one where progress is easier to notice.

The question is, then, how to approach opening study?

We have spilled some ink on openings already, but today we will look into an organizational question that can help you ease your opening work: why should you study openings for black first?

The reasons are simple, if not that evident. However, it might be useful to digress a bit.

The nature of the opening for Black and White

White moves first in chess. It’s such a significant advantage that symmetric play is easily punished.

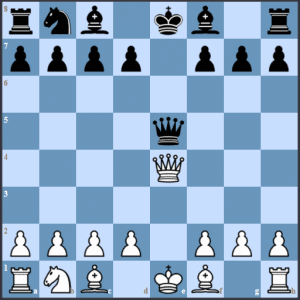

Take this – admittedly ridicule – Petroff Defense example: 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.Nxe5 Nxe4? (it was time to break the symmetry with 3…d6 and only then 4…Nxe4; Black would be fine) 4.Qe2 Qe7 (4…d5 5.d3 Black looses a pawn for nothing) 5.Qxe4 with a big advantage for White, even bigger if Black carries on with the symmetric 5…Qxe5??

You can compare the advantage of the first move, with serving in tennis. The player who serves strikes first. Even if their opponent defends well, they get to dictate the flow of the game for a while.

In chess, it’s the same. If White uses their extra tempo wisely (tempo is the time unit for moves on the board), they can quickly complete development and enter the middlegame. That gives Black little room for error. One wrong move could get them in big trouble.

The opposite is not true, however. Due to the extra tempo, White usually has a way to cool down the game if things go wrong. Thus, even a big mistake might mean only a slightly worse position, instead of a losing one.

So, Black’s margin for error is considerably smaller. This is most notable during the first few moves, as White’s pieces can get the best squares and start creating threats faster. But with correct play, it extends to the middlegame too. Even in closed positions, although not as much as in open positions.

The mindset of playing each color

Traditionally, White is entitled to turn the extra tempo into a tangible advantage, while Black needs to equalize before showing ambitions for more.

So when preparing their openings, both sides tend to dismiss lines that don’t meet the desired result. Equality for White is considered a failure, and a slight disadvantage means poor preparation for Black.

But, they both can’t achieve what they want. A position is either equal or preferable for one of the sides. Who is right then? Kind of both.

At this point, it seems pretty evident that the game of chess is a draw. The stronger engines get, their evaluations tend to equality, and saving resources appear all the time in seemingly hopeless positions.

While the draw rate could be much bigger than initially expected, White has more chances to exploit the opponent’s inaccuracies than vice versa. Therefore, from a practical standpoint, White is on the easier side of equality. It’s more comfortable to play with and has a wider margin of error.

So, while against perfect play, it should be impossible to get a significant advantage, White has reasons to try to press for more in the opening. Meanwhile, Black knows that going through the opening might be bitter, but the desired equality is realistically within reach.

All of this leads us to the three main reasons why you should focus on your Black Repertoire first.

Conciseness

Let’s say you play the Caro Kann against 1.e4 and the Queen’s Gambit Accepted against 1.d4. You might have to work a lot on the different variations White can throw at you there. But the rest of the stuff doesn’t bother you. You only need to work on two openings!

Being White is different. Playing 1.e4 means you must be ready for the Sicilian, the French, the Scandinavian, and when they run out of countries, there are still no less than four moves to care about – all of them with various systems and setups that you need to know. 1.d4 is no different. The King’s Indian, Nimzo-Indian, Grunfeld, Slav, and the Dutch are just some of the possibilities.

As Black, you considerably reduce the amount of theory you are required to know.

Practicality

While it’s easier to grow more fond of your white openings – after all, we all prefer to start the game instead of trailing – that’s precisely why you should pay more attention to your Black repertoire. It’s easier to get roasted with Black.

If you don’t know what you are doing – and sometimes even if you do – you can easily end up on the wrong foot when you’re playing Black. As you start a tempo down, your reaction time is shorter. So it’s better to secure a game with Black.

When you are White, you have more space to see what happens. If need be, you’ll likely find the way to steer the game towards a direction that suits you. But you will rarely be blown off the board in 20 moves.

Also, a Black repertoire is easier to keep up to date with than a White repertoire. Once you get your openings down, you’ll only need to make periodic, minor adjustments. Not that hard when your friends, the engines, can help you. In the long run, you’ll achieve the desired equality.

It’s not the same with White. Yes, you can use engines too, but you may be looking for something that’s not there (a path to an advantage). That’s a reason why you’ll find more Black repertoires on Chessable.

Psychology

Having good results with Black is a huge confidence booster. It means you can handle it where more people struggle. It also affects your opponents, who now don’t have a handicap against you in any way.

Psychologically, your mindset is more straightforward. You are not under pressure and don’t need to prove anything. For the first few moves, you just react to white’s play and try to get a healthy middlegame to grow from.

And amidst all the meta-theory, let’s not forget that chess is played by humans. Mistakes will occur. And the first player has the chance to err first!

Recommended reading

I’d kick myself if I didn’t recommend the incredible Chess for Zebras, a brilliant book by my favorite chess author, GM Jonathan Rowson, which is now available on Chessable!

In it, Rowson delves into obscure philosophical but practical matters. Some of them are improving your ability to improve and creating a set of tools to deal with the exponential jungle of chess possibilities.

But more importantly for our topic, an exploration of the dual identity of chess players as Black and White. You can learn a lot about your relationship with chess and yourself with this course.

Also, here’s an excellent guide on how to learn an opening. And if you need something more advanced, in a previous post, star Chessable author GM Alex Colovic detailed how he studies openings, which you sure will find helpful for either color or level.

FAQs:

What is the best opening move in chess for Black?

It depends on what White plays. Black has several good options against all possible first moves, so it’s a matter of taste. The guideline should be to develop as quickly as possible and fight for space. The best way to do so is to play towards the center to develop as actively as possible.

Basically, any big mainstream opening should do, and you can learn more from them below.

How do chess players open with Black?

Against 1.e4, Black has three main roads:

- a) dark-square strategy, claiming ground of their own with 1…e5 (Double King’s Pawn Openings) and 1…c5 (the Sicilian Defense), both preventing a perfect White center with 2.d4.

- b) light-square strategy, fighting back White’s advanced pawn with 1…c6 (the Caro Kann Defense) and 1…e6 (the French Defense), both preparing 2…d5. However, the direct 1…d5 is also popular (the Scandinavian Defense). They all question White’s center so that even with a White pawn in d4, Black’s piece will find squares in the center.

- c) the hypermodern approach, letting White grab space in the center to attack it with pawn breaks and piece pressure from afar. Examples are 1…Nf6 (Alekhine’s defense), 1…g6 (Modern defense), or 1…b6 Owen’s defense), among others.

None is better than the other, and their use depends on the player’s preference. Although it has to be said, the top players’ hierarchy of choice follows the order they have been cited above, and beginners would do well in emulating them.

Against 1.d4, the most popular move is 1…Nf6 (introducing the Indian defenses) because of its flexibility. It can lead to dark-square, light-square strategies, and hypermodern openings alike.

1…d5 (inviting to a Queen’s Gambit) and 1…f5 (the Dutch Defense) will mostly lead to a light square strategy by black (not always, though) and follow 1…Nf6 in popularity.

There are other moves that lead to hypermodern setups, but they are much less popular.

What does Magnus Carlsen play as Black?

In his youth, Carlsen played the Sicilian against 1.e4 the most (Najdorf and Sveshnikov variations mostly). However, since he became a Grandmaster, he has preferred 1…e5 going for classical main lines in the Spanish and the Italian Openings. He has used almost all openings throughout his career, but none enough to be considered ‘his’.

Against 1.d4, the Nimzo-Indian, the Queen’s Indian, and the Queen’s Gambit Declined have been fixed choices since he started playing, with some uses of the Grunfeld and the King’s Indian Defense.

Although they all have preferences, top players are well-prepared in almost all openings, and the World Champion is no exception.

Are chess openings for White or Black?

Strictly speaking, White’s first move will determine the opening, and Black will choose the defense. Then, depending on the specifics, both sides can decide the variation or system.

However, defenses and systems are still openings (it’s not wrong to label the Sicilian Defense and the King’s Indian Attack as openings). We only name openings that are often played because their theoretical analysis is relevant for establishing the best first few moves of the game.

Broadly, the opening is the first phase of the game. It lasts approximately for the first 12 moves (give or take, until both sides finish their development and meet the opening’s principles).

Also, it is possible to reverse openings (usually, if white wants to play a black setup, they can do so with an extra tempo). So 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d3 could lead to a reversed Philidor, and 1.c4 e5 is a reversed Sicilian. Interestingly, though, what equalizes for Black doesn’t necessarily lead to advantage with White.