The Aging Chess Player – Revisited

If emailed feedback from Chessable users is a reasonable proxy for interest, then my post on chess and aging from a few months ago hit the spot more directly than any other of my science blog posts so far. I was fascinated by the personal stories contained in these emails, and I asked one such respondent, Trevor Harley, to write a follow-on piece relating to his personal and professional knowledge of the impact of aging on cognitive performance.

Trevor is Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Dundee in Scotland. His research interests in cognitive psychology are varied (see www.trevorharley.com), but include the aging process, and Cattell’s distinction between fluid and crystallized intelligence (the former peaking in one’s early 20s, whereas the latter increasing or remaining stable until around 65, with a gentle decline thereafter – but with these average ages buffeted by a wide variety of factors such as domain of expertise, practice regimes, individual differences, etc). Trevor is author of several books, the most recent of which is The Science of Consciousness (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

He describes himself as “a distinctly average chess player, competent at beating players rated lower than him, and even more competent at being beaten by players rated higher.” His awareness of his metacognitive abilities is still improving, and he “knows that he doesn’t eat enough oily fish”!

I hope you enjoy this wise and deeply personal account, which also touches on the subjects of other science blog posts – e.g. metacognition, patience, and diet. As always, I welcome feedback to [email protected], or alternatively directly to Trevor via his website.

Professor Barry Hymer

Some Crystallized Thoughts from an Aging Chess Player

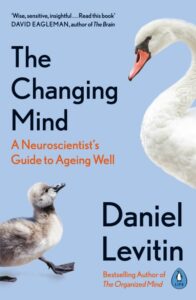

My name is Trevor Harley. I am 62, and I think I think the same way as I did when I was 26. This belief is wrong. I am a cognitive psychologist who has worked on aging for many years, and I know that as we age our abilities change. Most people start aging cognitively from their mid twenties. The frontal lobes of the brain, responsible for planning, judgment, thinking, and reasoning, and central to playing good chess, continue to develop throughout adolescence, and only mature around then. It is no coincidence that mathematicians and chess players are at their best around that age.

At 26 I was at my peak. Working memory starts to decline then, with forgetting typically accelerated around 65. At 62 I have noticed a few signs that my memory isn’t what it was: not being able to remember some names, forgetting where I put my keys, and forgetting what I had just decided to do (prospective memory). It’s important to note that cognitive decline is normal, and doesn’t mean that you have Alzheimer’s disease (although of course if your memory loss feels abnormal, you should check it out).

62 – Better Than 26…?

I often wonder what would happen if my 62-year-old self played my 26-year-old self. When I was young my rating was 1800; now it is 1450. That difference isn’t wholly due to aging because I took a break from chess for many decades. Yet in spite of my lowly rating I feel like I’m a much better player now.

I remember making several terrible blunders when young, but when I was getting closer to age 18 I think they became less common – they must have, if I reached 1800. I don’t remember being particularly good at tactics, but again I must have been OK. So on paper my younger self would easily beat my older self.

There is of course a debate on whether there is rating inflation, but surely the average club player has to be better now than the average player of a few decades ago? Just look at all the resources the Internet has to offer, including a game whenever you want it.

Slowing the Decline

It is also important to note that these numbers are averages, and we can do much to slow down our decline. Basically what is good for the body is good for the mind: a healthy diet and exercise (I could write a whole post on my daily chess supplements), particularly exercise of the sort that improves blood flow to the brain. There is now much evidence that cognitive exercise slows down aging, which means that playing chess in itself has a neuroprotective effect on declining chess abilities.

Aging isn’t all bad news. While aspects of intelligence such as speed of thought and working memory capacity might decrease, what might be called “wisdom”, our available pool of knowledge, increases. Our ability to reflect on and change our behavior – what we call our meta-cognitive ability – also improves with age. Like many youths, I didn’t reflect much at all when I was a teenager: my metacognitive abilities were much weaker. Older chess players should put these reflective skills to use.

War Against Sleep

The mystic Gurdjieff taught us to fight the “war against sleep”. He didn’t mean sleep was a waste of time (it’s not); he meant that we should be aware of being aware. In modern terminology he’d say that we should be mindful of our consciousness. Gurdjieff didn’t mention chess, but he could easily have been writing about it. I am aware of the war against sleep over the chess board.

When I was 18, my playing was highly reactive. I don’t think I had a chess thinking system at all, though I do now. I don’t think I even thought about whether I had a thinking system. But then few young people do, especially without coaching, and awareness of such things is another advantage of age.

I know that if I continue to think about playing as well as just playing, I will continue to improve, and protect my mind as well. But I know there are limitations on how good I can be. I’ll never be world champion, or a grandmaster, or possibly even a 2000+ player. Some might find these limitations liberating because it means we can play just for fun. When I was young I thought, if I thought about it at all, that the sky was the limit, but now I have my feet on the ground, quite close to six feet under.

Practical Advice

Think of your brain as a muscle that needs regular exercise to stay young and healthy. All cognitive exercise is good, but the more domain-specific the better, so one of the best ways of keeping your mind fit for chess is to play plenty of chess.

Fighting cognitive aging is mostly common sense. Get plenty of sleep, and take regular exercise. Don’t smoke. Eat well, but not too much. There is a MIND diet which is similar to the Mediterranean diet and the diet for heart health.

Be mindful in general (because it’s good for mental health), and be chess mindful in particular. Use your enhanced meta-cognitive skills to your advantage. Slow down when you play – let the young rush and make mistakes – and develop a thinking system and apply it every move after you are out of your opening.

Further Reading

Greenwood, P. M. (2007). Functional plasticity in cognitive aging: Review and hypothesis. Neuropsychology, 21, 657–673. Read this paper if you want a flavour of the more technical literature.

For recent books on aging in general:

The Changing Mind by Daniel Leviton (Penguin, 2020)

Ageless by Andrew Steele (Bloomsbury, 2020)

…and, of course, remember to visit Trevor Harley’s website.