Impatient to improve? We all know the feeling.

Your weekend reading is here, as we return to the fascinating world of science with a new post by Professor Barry Hymer, our Chessable Science Consultant.

Paying attention to our diet is similar to the art of finding time to study endgames. They are both things we know we should do, but somehow the advice is much easier to give to others than it is to follow for ourselves.

In this important new post, Professor Hymer investigates, among many other matters, the impact of our diet on our play and what we need to learn from endgames. Pull up a pineapple, pass the chocolate and take your time to read all about the power of patience.

Over to Professor Hymer…

Impatient to Improve? That Could Be The Problem

“When you see a good move, look for a better one.” (Emanuel Lasker)

One of the features of science is that it extends its tendrils into the most unlikely domains of human achievement. With so much emphasis on the remarkable developments in Artificial Intelligence specifically and in learning technology generally, it is easy to lose sight of the science behind human character strengths and virtues, like courage, wise judgment, and originality. The celebrated social scientist Martin Seligman built his reputation by studying qualities like these in considerable detail, and we will be exploring many of them ourselves in future posts. On this occasion though I’d like to examine some of the science behind – and role of – patience in chess improvement, and tentatively suggest a few ways in which we can develop and harness this quality in our own play, and in our Chessable practice.

The Value of Patience

Of course at one level we already know the value of patience in chess. From our first forays in the game we’ve all at some point been advised to ‘think before moving’, to sit on our hands in ‘won’ positions, and to look for a better move when a good one presents itself. And yet we’ve all still fallen foul of this sensible advice too.

Which of us hasn’t acted on a rush of blood to the head at the first glimpse of a brilliant sacrificial attack, neglecting the solid defensive or counter-attacking resources that our opponent could call upon? Or tried too hard to force the pace, or asked too much of our position? The net result is another sleepless night reliving the horror of thrashing out with a desperate and unsound lunge in response to our opponent’s attack and succumbing meekly in the process, or the frustration of blowing an advantage in the rush to convert it into a win.

Boosting Enjoyment

Is it possible to make a scientific analysis of these instances of patience-deficit? In many ways, we can. Let’s begin with our bodily chemistry. Through its reward features Chessable has already sought to harness the power of endorphins (a neurochemical) in boosting enjoyment and motivation, but researchers have demonstrated the pivotal role that the neurotransmitter serotonin plays in a number of emotional, cognitive, and behavioural control processes (Cools, Roberts, & Robbins, 2008). This role is well-established in such areas as appetite, mood, and sleep/wake behaviour, but there are others that are even more clearly of interest to chessplayers – such as cognition, memory, reward, anxiety, and learning itself (see this interesting article, for example).

Serotonin and Patience

But serotonin also seems to have a specific role in combating impulsivity and promoting patience – although it’s worth noting that we don’t currently have a clear understanding of the neurological process for their regulation. As a result, recent research has concentrated on exploring how serotonin acts on specific regions of the brain to regulate the ability to wait for a desired reward. The finding of a causal relationship between a brain region and patience for anticipated rewards, and that two areas of the brain seem to work in tandem to combat impulsivity in response to serotonin offer hope for developing targeted treatments for impatience and impulsivity.

Many of these studies into ‘the patience effect’ involve laboratories, controlled conditions, and mice, and it would be a stretch to suggest that there are clear and immediate extensions we could make into chess practice. But we do see their manifestation in naturalistic human behaviour too: our relative patience in shopping queues and traffic jams if we have confidence that we’ll be attended to fairly and successfully – even if we don’t exactly know when, but our impatience and barely suppressed rage if we feel service is a function of sharp elbows, aggressive driving or random chance.

Of Mice and Memory

One of the studies asked the question, “Would mice wait for food regardless of the probability and timing of it turning up, or would they give up if they predicted a low chance of return on their time investment?” What emerged was that when food was presented at regular intervals, serotonin had minimal effect on the mice’s patience/preparedness to wait, but when the reward timing was unpredictable, serotonin had a significant effect on their preparedness to wait.

So here’s my hypothesis: since the result of a game of chess is a clear instance of unpredictable reward timing (without illegal assistance, we don’t know the result, course or duration of a game at its outset, and would surely lose all passion for the game if we did), serotonin is likely to be important in helping us to approach the game calmly and rationally and patiently.

And this begs the obvious question, what can I practically do about this? Here are a few suggestions.

Mind Your Diet!

There are no foods that contain serotonin itself (since it’s made in the body via a process of biochemical conversion), but its building blocks (especially the amino acid tryptophan and the converters) are to be found in certain foods and vitamins, especially whole grain cereals, sardines in oil, lean meats, eggs and dairy produce, legumes, nuts, fruit (especially pineapples and bananas), seasonal vegetables and, hooray, dark chocolate. Polite notice: Tournament Directors everywhere would ask you please not to bring all of these foodstuffs to the tournament hall, but a diet generally rich in these could help you find the calm and strongest move in this position, much used by my friend and co-author, Peter Wells, in his training work with junior players.

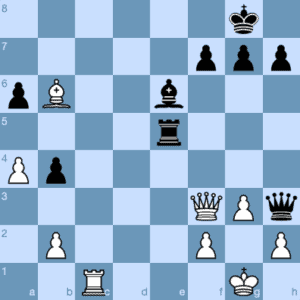

Black to Play

Answer: the pineapple-enriched 1…h6! is crushing, as in anticipation of the devastating 2…Bd5 White is forced into 2.Qg2, a queen exchange, 3…Re2 and a long defence of an unpleasant ending. Instead, the caffeine-fuelled 1…Bd5?? fails to 2.g4!, after which Black can resign.

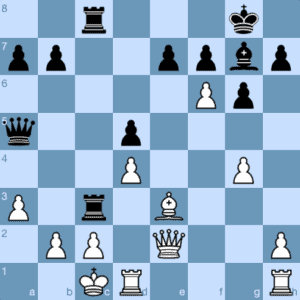

White to Play

And what patience-oriented diet allowed Mark Hebden to find the serene 22.Kb1! in his game against John Nunn at Hastings 1997/8?

The game finished soon after: 22…Rxc2 23.Rd2 and a black piece must drop. 1-0.

Ignite Your Metacognition

Beyond a good diet, we can also choose to ignite our metacognitive powers before and during a game, getting ‘above’ the cut-and-thrust of the game itself to self-regulate on the process of playing it. The experienced chess teacher Tim Kett reminds his pupils to enjoy the pleasure of savouring a winning position – “They need to renew their focus, check carefully all the things that could go wrong, stop banking on the result, remind themselves that they’re enjoying the problems their opponents are still setting them, and that they don’t want it to be over yet” (Chess Improvement by Hymer & Wells, page 258).

Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There!

The history of chess achievement is as much a triumph of sitzfleisch as it is of bravura displays of brilliance. Steinitz in his mature years, Botvinnik, Petrosian, Karpov, Kramnik, Adams, and of course Carlsen were or are masters of patient prophylaxis, quietly improving their pieces whilst waiting for their opponents to “show their chess personality” – in the inspired words of the composer and IM Yochanen Afek to Peter Wells, when Peter expressed his frustration at failing to put away an opponent with more direct and forceful methods.

Learn From Endgames

We all know (theoretically) that a study of the endgames can be one of the surest routes to chess improvement, but one of the most important meta-learnings is from the observation that the technical conversion of small advantages in the endgame necessarily requires patience – the value of making slow progress via many precise moves is starkly apparent – more so than in many middlegame positions where there are too many other ‘factors to consider’. If you haven’t already encountered the Centurini Position, for example, take a dip into Theoryhack’s stimulating free course, Basic Endgames, to enjoy the painstaking logic of this win, and many others. They just won’t be rushed.

Play With Your Settings

Chessable gives us a great deal of agency when it comes to how we tackle our studies, and it’s time well spent thinking about how you can personalise your settings to suit your current skill levels and preferred approach to learning. For instance, I have recently started enjoying Malcolm Pein’s free course, Telegraph Tuesday, but the default time allowance for solving most of the positions presented is far too tight for me. I found myself lurching impulsively from one fail to another, as if I were in a state of permanent zeitnot.

Upping my allowance to 180 seconds per position has allowed me to approach the task far more thoughtfully and productively, getting my initial bearings in the position, checking out decent candidate moves, correcting for false positives, and ultimately extracting far more benefit from the exercise.

Science’s Roots: Natural Philosophy

Finally, let’s remember where our modern understanding of science comes from – a wish to understand nature shared with the ancient discipline of philosophy. So let’s draw on both Western and Eastern philosophical traditions in observing that patience begets patience: the practice of acting patiently will make it easier to summon over time. As Aristotle taught us, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, therefore, is not an act, but a habit.” Or in the wise Eastern proverb, sit by the river long enough, and the body of your enemy will come floating by. Enjoy the wait.

As always, I’d welcome feedback to [email protected]